This post is part 3 of 3 in a brief series on creating video for those with disabilities. I’m no expert, but can at least offer some suggestions for creating video that’s more accessible. Our goal: to create content with Universal Design in mind. If you need more guidance or are interested in learning more, I’d recommend that you engage a specialist.

You may not have a product or service that is geared directly toward those with disabilities. But perhaps you do. Either way, we know that video does a great job communicating and is the preferred way to reach people online. And we don’t want to exclude a part of the population from experiencing this.

How often do you think about the large portion of our population that lives with some disability? Have you ever thought about how you might design video for these people? What’s their experience like?

And, more specifically, how can we make video accessible to those with cognitive disabilities?

Definitions

When I’m discussing ‘cognitive disabilities,’ I’m generally referring to individuals that have “limitations or challenges in performing one or more types of cerebral tasks” (description borrowed from the FCC). More specifically, ‘cognitive disability’ is defined as “a term that refers to a broad range of conditions that include intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders, severe, persistent mental illness, brain injury, stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.”

For the purpose of this article, it also includes everything from epilepsy to dyslexia to learning difficulties.

And, “according to the website of the Coleman Institute for Cognitive Disabilities, an estimated 28.5 million Americans, more than 9% of the U.S. population, had a cognitive disability in 2012” (italics mine, quoted from the FCC). That’s a significant portion of the population!

The Problem

Some of the cognitive disabilities that people experience cannot be easily designed around in video. Since the spectrum we’re dealing with is much larger than the previous 2 articles, we can only handle so much. This does mean, unfortunately, that we need to accept that our videos won’t be accessible to some.

That said, we can still design for accessibility. Rather than laying out specific solutions or tested treatments in this article, I’d like to outline some principles. If you generally keep to them, you’ll still be able to freely create video (and focus on the storytelling), whilst allowing room for those with disabilities.

Keep a Low Sensory Load

Several people with cognitive disabilities have trouble processing their environment. They can be overwhelmed by the visual activity on a screen, whether that be bright lights or lots of things happening at once.

Those with more severe challenges, like Autism and Photosensitive Epilepsy, are most affected by this. Even those who experience migraines fall into this category. Fortunately, we can design for this.

Although a story may call for it, quick flashes and regular moving patterns are hard for those who have sensory load problems. Intense, blinking lights may cause these kinds of people to suffer pain or confusion. Thus, when crafting your video, you should remove these kinds of rapid or random sensory changes.

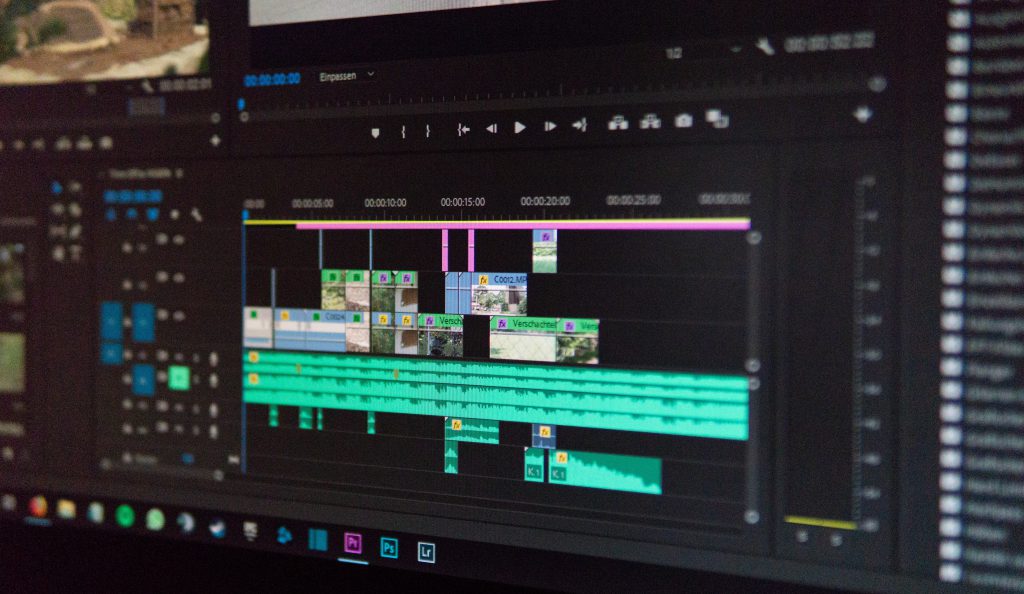

You can use the Harding Flash & Pattern Analyzer software to test your video on this principle. This will help you determine if your video complies with the international guidelines around sensory load. Per their website, when a video does fail a test, they “provide detailed frame-by-frame results in visual ‘heat map’ and tabular form, to enable you to fix it creatively, without degrading your content.”

Ensure Text Reads Clearly

Whenever you display text in your video, whether that be a shot of a handwritten note or an over-the-shoulder of someone texting, it must read well. Otherwise, people who struggle with disabilities like Dyslexia will have a hard time keeping up.

It’s best to avoid situations that require the audience to see something written like this. If a character is quickly scrawling a note or looking briefly at an official notice, it would be best to reiterate what’s being seen. You can do this through a comment in the audio, a subtitle, or a more creative method.

Regarding phone texts, there are several creative ways to show these, rather than simply shooting an iPhone over someone’s shoulder. The show Sherlock, for example, does a great job creatively blending “floating” text into the environment around the character. You could also create some simple, clean animations that show the audience what a character is reading. Most of this can be handled by the professionals.

“Text” also includes subtitles or captions (as we wrote about in Part 1), but those are already pretty standardized. Generally, text should be placed on solid backgrounds with good fonts. If the text you’re shooting has a clean and easily readable font, plus a solid or dark background, you’ll generally be okay. There’s plenty of other articles and specific guidelines on this point, so do some more research if you’re curious.

Simplify or Clarify Visual Information

Those who struggle with executive functions have a harder time receiving, processing, or acting on information. In some cases, it takes a longer time to walk through those steps. In others, there are severe impairments that halt or stop portions of the process.

To make your video accessible to these people, you should generally try to simplify the information on the screen. You want to ensure clear visual design with definite visual cues. Like with sensory load, you’ll want to ensure that what someone is supposed to be looking at (or perceiving) is obvious. You’ll want to direct the viewer’s gaze effectively. Fortunately, this is a basic concept in visual aesthetics, and you can let us handle it for you.

Depending on the kind of story you’re telling, you could also add in simple reminders of what’s happening on the screen or in the plot. “Double reminders” like a character repeating in dialogue something that we’ve just seen can be helpful. Redundant visuals could also be a good step toward keeping your video accessible.

When focusing on accessible, universal design, it’s always best to get your video in front of those who actually struggle with the issues you’re designing for. Especially since cognitive disabilities are so varied. Although there are plenty of smart people who study and recommend best practices, testing is always a crucial part of making something accessible.

As we’ve seen, however, there are a lot of small changes that you can make for more universal design. There are also principles by which you can create that will keep things accessible in the majority of cases. Although not directly applicable to video, you may find UK Home Office’s Accessibility posters helpful to reminding you how to be accessible across several disabilities.

If you start thinking about how to make your video more accessible from the start, you’ll be opening the doors to a wider potential audience. And they won’t feel shoehorned in, as you’ll be designing with accessibility as a focus in the beginning.

Good luck! Don’t be afraid to engage a specialist for further help.